We follow the swing that the narrator took in “Bitter Orange” by the Lebanese writer Basma ElKhatib (Dar Al-Adab) as a deceptive, rotating place from which she appears to tell, between a backward jolt that overlooks a past in which the most painful thing is, and the most beautiful thing in it is almost absent, and a forward jolt that overlooks a mysterious future for an expected person, as if he came from fairy tales, for whom the women of the world prepared a history of meals on a table thirty years long.

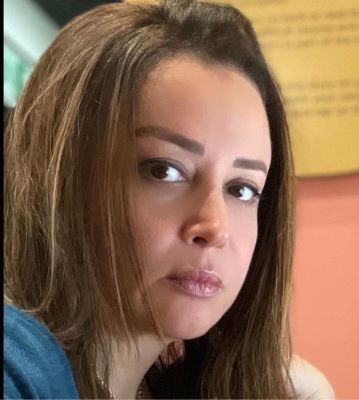

Basma ElKhatib

This swing represents a narrative formula between more than once, and under more than a single sky, in a time space relatively close to our present, and in a somewhat similar geography in our Arab East.

In her first novel “Bitter Orange,” the Lebanese writer Basma ElKhatib chose to be that voice that records – for the last time – secrets that time has erased, after wars have swallowed them, and nothing is more painful than the secrets of suffering women, embodied by the heroine of the work/narrator who is approaching the completion of her third decade.

All the revealing secrets revolve around food, inside and outside the kitchen, and sometimes link women, sometimes men, and even peoples: “The Palestinians lived with us for a long time, but their Molokhia (a liquid dish prepared as a green soup of plant leaves ) did not enter our homes. We kept calling it “Saita,” and we did not enjoy “Musakhan” (Musakhan, also known as muhammar, is a Palestinian dish composed of roasted chicken baked with onions, sumac, allspice, saffron, and fried pine nuts served over taboon bread.

Originating in the Tulkarm and Jenin area, musakhan is often considered the national dish of Palestine) under the pretext that it wasted our sumac supplies! We lived with them and intermarried with them, but cooking is something else. It is not a matter of arrogance or racism, but perhaps it is a matter of timing. They lived with us in the middle of the twentieth century, and that was a time when we were lazy about diligence and development. Perhaps setbacks and defeats entered the kitchens, and made the art of cooking a luxury that women did not dare to do. And certainly the war killed the appetite for innovation and the tradition of renewal, so our immigrants tried to balance the issue, and in their migration they cared about the dishes of the burning homeland.”

In contrast, the writer, through her heroine, satirizes all processed meals and all the waste of the global kitchen, and belittles any meal that does not come from the traditional kitchen:

“Pizza is stuffed with cheese, but with olives, tomatoes and greens added to it, and the hamburger is a round meat sandwich, that’s the whole story… no invention, nothing.”

As for mortadella, it is just “meat shells, skins and fat… animal waste,” which is what she used to say to the women of the neighborhood when they asked her for cans of mortadella from a canning factory where she worked near the city of Sidon.

Basma ElKhatib excels, through her narrator, in bringing secret recipes for an almost extinct foods, as if she is writing an encyclopedia of nostalgia for a history in which food was delicious, and life was delightful. But she is also creative in inventing other recipes for people, using food supplies in kitchens. For example, we read how she describes the air conditioning maintenance worker as being thin, “like a green mint leaf in a cup of hot tea.”

While she hates her mother, the narrator loves her Aunt Fatima’s fiancé, since she lived with her in the grandmother’s house. The aunt, whom the fiancé replaced with a brown-haired Russian wife, like most Russian women brought by the village’s young men when they returned from their fruitful university studies, collapsed in bitter tears on the night that “the awaited one” broke off his engagement to her!

But Fatima’s love, which died when her husband left, did not die in the narrator, but rather grew along the days and years, since she used to hide his diaries, or any of his pictures under her pillow, or steal his smell and touch, while her heart was throbbing as she looked at her aunt’s bed, unable to guess her reaction “if she discovered that the poisoned dagger that stabbed his heart was under a pillow three steps away from her.”

This fear of Fatima and her reaction crossed the distant past to the night of the appointment with that mysterious man, whom she whispers to, and who has not yet come: “What if she attacked me now, and knew that I invited you, and discovered that I have loved you since my early years, and that I did not only share with her the tragedies of orphanhood, loneliness and solitude, but also the love of the same man.”

The novel is full of loss, bereavement and absence, and the events are hostage to waiting for what does not happen and who does not come. It does not only concern meals and cooking recipes, but also concerns people, as well. There is Taym, the absent man, whom she almost postpones the appointment to meet, and there is also the infant who was lost by his Kurdish mother and she also disappeared searching for him, and we have the Palestinian freedom fighter Hassan, whose mother died in the Al-Bass camp in the city of Tyre and his clothes were buried with her, as she requested.

I know the writer’s passion for her grandmother’s stories, even before she published her novel, and her love for her popular heritage, a passion that fermented like a loaf of local bread to ripen as the seduction of bread ripened, which she learned from her grandmother, as if she was handing her one of the keys to life with its asceticism and worldliness.

For a few moments – while reading – the words of the novelist Isabel Allende in her text “Aphrodite” passed through sensual food recipes that the Chilean writer linked to lust, and erotic rituals for the goddess of beauty and desire among the Greeks, but the contrast and the objective equivalent were lost when the shyness of the narrative of an Arab girl who carried her naivety with her and her innocent ideas from the village that gave birth to her emerged, and she would not create her parallel world except to revive history, and not to arouse the reader’s lust.

The young villager lived for many years with visible and hidden scars, from past and present wounds, her unknown name became for all women, her unknown house became a reference to all villages, her hidden pain became a symbol of the paths of human suffering, and her only hope that she prepares for became the reader’s hope in a savior who realizes that his presence may save the narrator and her world at the same time.

Here she is preparing herself for him, until she gets lost in her new home, and in the heart of the confusion she talks about him, with much love and criticism, and in the midst of the belief that he has departed, and that she has washed away his memory with the rain that suddenly fell, she returns to meet together at the doorstep, and he calls her by her name that we read for the first time in the novel, and it appears in her last words, as if she found her identity when he pronounced it.

The novel, published by Dar Al-Adab (2015), had its cover designed by the artist Najah Taher, and it featured one of her paintings; a swing as a visual equivalent to the narrative game (a picture of a real swing was added instead of the first drawing, as if this came in the context of the present of illustrated globalization versus the traditional drawn heritage) in a novel that opens up the world of women from the corner of the kitchen, to take us into worlds of dreams of clouds trying to rain towards the orchard of hope.

Comments