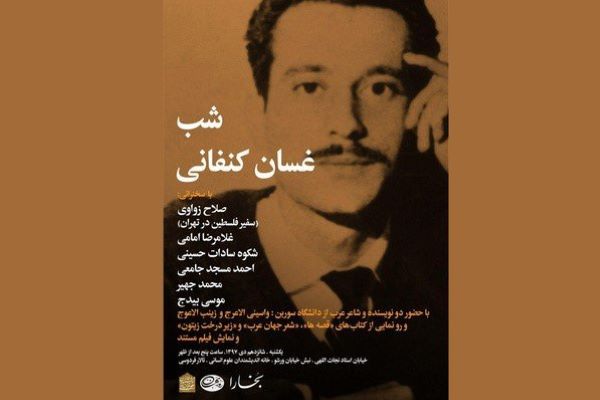

Ghassan was 36 years old when he died along with niece in a bomb explosion planted in his car in Beirut on July 1972

In Beirut, on July 9, 1972 – Ghassan Kanafani climbed into his Austin 1100 car with his 17 year old niece Lamees, switched on the ignition and triggered a bomb planted by the Israeli Mossad. He and Lamees were killed instantly. But who was Ghassan Kanafani and why was the Israeli state so determined to kill him?

Ghassan was an iconic Palestinian writer, journalist, artist and political activist whose life was inextricably linked to key moments in the Palestinian struggle. At the time of his birth in Akka in 1936, Kanafani’s father was an active participant in what became known as the Palestinian Arab Revolt from 1936 to 1939. Palestinian Arabs were resisting the British Mandate occupation of their land and British complicity in the Zionist colonization of Palestine. The goal of establishing a “Jewish National Home” had been promised to the Zionists in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. The Arab revolt included a seven-month long general strike and an uprising that was brutally suppressed by the British military. Ghassan’s father, who was a lawyer, was imprisoned by the British on several occasions while Ghassan was still a child.

Life in Exile

When the 1948 Arab-Israeli War broke out news of the Deir Yassin Massacre reached the Kanafani family. Zionist militias had murdered 254 villagers on the 9 April 1948, the day that Ghassan turned twelve. He never celebrated his birthday again. The family fled to Lebanon and then Syria joining hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians exiled from their homelands during the Nakba.

The family settled in Damascus where Ghassan completed his secondary education, like many refugee Palestinian children, in an UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) school. He gained a teaching certificate in 1952 and was employed as an art teacher for some 1,200 children in the refugee camp. It was at this time that he began writing short stories to help himself, and his students, make sense of their situation. In fact it was Kanafani who later coined the term resistance literature to describe a genre of writing that encouraged its readers to recognize their oppression, to resist and fight together for a better future.

Ghassan’s higher education was at the University of Damascus in the Department of Arabic Literature. However, before he could graduate, he was expelled and exiled to Kuwait for his political ties with the Movement of Arab Nationalists (MAN), a pan-Arab nationalist organization inspired by Gamal Abdul Nasser’s ideas of national independence. The Movement of Arab Nationalists was founded by Dr. George Habash in the 1950s and would later, after the 1967 Six Day War, develop into the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Ghassan moved to Beirut in 1960 where he deepened his interest in socialist philosophy and revolutionary politics. It was in Lebanon in 1961 where he first met his wife Anni Høver, a Danish journalist who wanted to find out more about the plight of the Palestinian people. She had been given the telephone number of a newspaper editor – Ghassan Kanafani – and was told he would be her best guide to the Palestinian cause. She met with the tall, lean 25 year old Kanafani and asked if she could visit the Palestinian refugee camps. He famously replied, “My people are not animals in a zoo,” adding that, “You must have a good background about them before you go and visit.” Two months later, they were married. Anni began teaching at a kindergarten in a refugee camp and Ghassan continued to write.

Turning point in Ghassan’s writing and political career

The 1967 Six-Day Arab Israeli War, and subsequent Israeli occupation, was a turning point in Ghassan’s writing and political career. Immediately after the war George Habash founded the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In 1969, Ghassan became its official spokesperson and editor-in-chief of the weekly newspaper Al-Hadaf. Although Ghassan was not directly involved in it, the PFLP had a military wing and was committed to armed struggle. Today we have to see this commitment in the context of the shock waves created in the refugee camps by Israel’s brutal occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. And in the historical context of anti-colonial struggles for national liberation sweeping across the world: including Cuba, Algeria, Mozambique and Vietnam. Even in the West, during the 1960s, there was talk of revolution in the streets of Chicago, Berlin, London, Paris and Tokyo.

The Israeli state saw the Palestinian resistance movement as an existential threat and moved to silence its leaders. It began implementing Operation: God’s Wrath, under the command of Prime Minister Golda Meir’s Special Adviser on Security Affairs, General Aharon Yariv. The aim of the operation aim was to eliminate Palestinians capable of providing leadership to the movement.

“I write well because I believe in a cause, in principles”

Ghassan was close to and wrote several poems and stories for his beloved niece Lamees. The day before his assassination Lamees asked him to concentrate more on writing stories rather than his revolutionary activities. She said to him, “Your stories are so beautiful.” He answered, “Go back to writing stories? I write well because I believe in a cause, in principles. The day I leave these principles, my stories will become empty. If I were to leave behind my principles, you yourself would not respect me.”

When he died Ghassan was 36 years old, Lamees was just 17. Today, his writings remain among the most influential in modern Arab literature. His works have been translated into 17 languages and published in 20 countries.

Ghassan’s obituary in the Lebanese Daily Star described him as, “…a commando who never fired a gun, whose weapon was a ball-point pen, and his arena the newspaper pages.”

His wife Anni still lives in Lebanon and heads the Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Foundation that runs kindergartens, children’s libraries, centers for children with special needs and other children’s activities in six of the twelve Palestinian camps in Lebanon.

On the literary life of a rebel

At first thought, the assassination would seem absolutely horrific, but when a reader starts to go through his novellas and short stories, as well as, of course, his articles on politics and the situation of the Arab and Palestinian cause, it would make perfect sense that he was a great threat to the Mossad with his fearless thinking, free of any shackles or boundaries.

In an interview, answering a question regarding the relation between his political life and being a novelist, Kanafani had replied: “My political position springs from my being a novelist. In so far as I am concerned, politics and the novel are an indivisible case, and I can categorically state that I became politically committed because I am a novelist, not the opposite.”

Kanafani’s love to his home was so clear and vivid. One time he said: “Do you know why most writers love Paris? Because they never lived a day in Haifa.”

Indeed, his novellas and short stories, almost all of them, had something to do with the notion of ‘home’ and the idea of patriotism and war. Many of his works also focused on the Palestinian struggle through life, even when immigrating and living outside of their country.

This is what the novella “Men in the Sun” discussed. The idea of this work revolved around the illegal ways of fleeing the country and the struggle immigrants go through. The shocking ending of this novella makes you want to scream out loud.

What distinguished Kanafani’s works is that their endings always carry something either extremely heartbreaking, or extremely unfamiliar and bizarre. There is always a guessing that the writer wanted so much thinking from his readers. He never wanted them to be just readers; he wanted them to literally live the Palestinian struggle as it is written through his painful words.

One of the most well-known novellas for Kanafani would be “Returning to Haifa”; it revolved around the idea of home, and the way that being raised in a family will make you who you are now or later, an idea that resonates in any mind, to think that it is not we who shape ourselves, but life. It talks about the very desolate and melancholic side of war, like most of his other stories. But this one, this one in specific will not be just a book a reader reads and places back on the shelf for dust. It is different, and this is the further one can go with spoiling. Perhaps one of the most mind-blowing quotes a reader reads within the book would be:

“Do you know what home is, Safiyya?

Home is where all of this wouldn’t happen.”

When you read too much for Kanafani, the notion of ‘home’ will not leave you for a second. It’s true that home is where all of this wouldn’t happen, where all of this shouldn’t happen. It wouldn’t possibly be that easy to know what home really is, but you’d know that home really isn’t the place where you see this too much suffering and hear all these depressive stories on war and defeat or occupation.

A few days before his assassination, Kanafani wrote what was soon-to-be his last article on the political situation in the Arab world. Here is one of the strongest lines in the article:

“There must be something in the way Arabs were created that would make them so different from foreigners, especially Zionists. The reason for this is that David Elazar, Chief-of-Staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) at that time, was very polite when he expressed his regret for the death of civilians during an Israeli air raid on Lebanon, because this cannot be avoided. These words, in fact, were a complementary part to the Israeli motto raised so high saying that ‘a good Arab is a dead Arab’.”

Reading these words, a reader would not make a second guess as to why Kanafani’s life was a cause of threat to all politicians, not just Israel.

Kanafani’s last words on the article were that “what we now hear from Arab officials is only bleating”.

So, after all of this, do we know what home really is?

_______________

Published under International Cooperation with "Sindh Courier"

Comments