Aryans conducted raids on Harappan, (Dravidian) cities, compelling the locals to toil in the fields to provide sustenance for their conquerors

Introduction

The cultivation of plant life enabled the Ashurs (Dravidians) to establish enduring cities equipped with proper irrigation systems to sustain agricultural practices. The domestication of rice and other crops offered respite from the nomadic lifestyle they led following the conclusion of the ice age. In contrast, the Aryans, accompanied by their cattle, roamed from one place to another after departing from Arjika in Kazakhstan. Upon mastering the domestication of horses, the Aryans conducted raids on Harappan, (Dravidian) cities, compelling the locals to toil in the fields to provide sustenance for their conquerors.

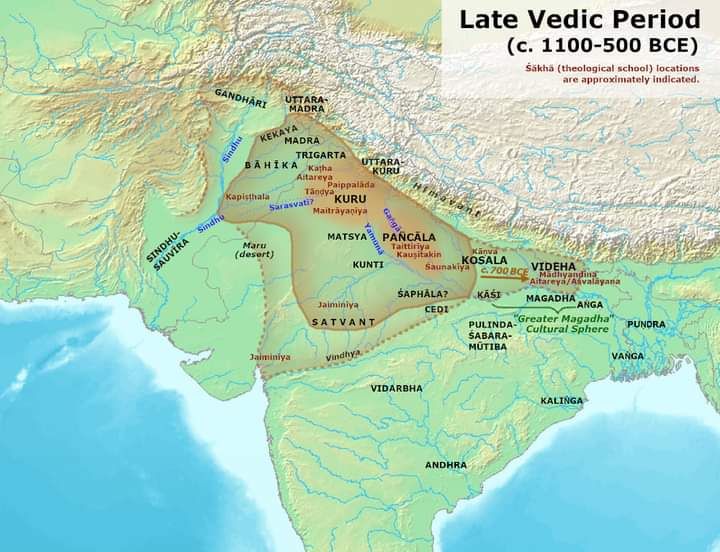

Eventually, with the cooperation of those who had accepted their subservient status, the Aryans founded new settlements along the Ganges. They referred to the territories under their dominion as ‘Aryavarta’.

The Aryan Onslaught: Videha’s Triumph and the Rise of Mahā-Videha and Vajjika League in Ancient India

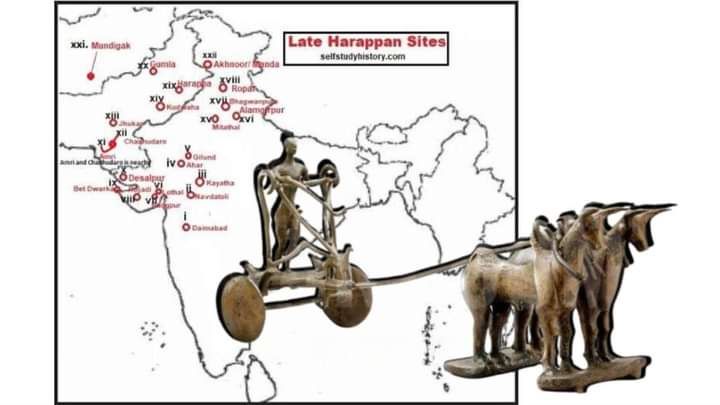

The influx of Aryan tribes into India led to the decline of Harappan cities. Among these tribes was the Videha, whose Prākrit name, Videha, conveys the meaning “without walls or ramparts.” This epithet was employed to signify the “destroyers of walls and ramparts,” as the Aryan Videha tribes dismantled numerous small Harappan cities, claiming them as their own.

Around 800 BC, in the eastern Gangetic plain, the Videha tribe established the cultural expanse of Greater Magadha, evolving into the Mahā-Videha (“greater Videha”) kingdom. Positioned between the Sadānirā River in the west, the Kauśikī River in the east, the Gaṅgā River in the south, and the Himalaya mountains in the north, this kingdom flourished as a significant regional power.

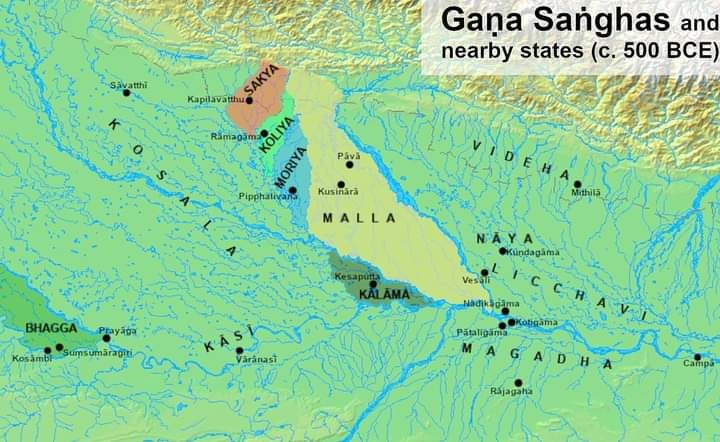

The Licchavikas, another Aryan tribe entering India, established a republic south of the Ganga in Vesālī, with support from the Jain Assembly and local aristocrats. Expanding their territories into Magadha, they named it Mahā-Videha and implemented the Harappan system of governance, characterized by a republican nature, known as the Vajjika League (Mahājanapadas) — an ancient Indo-Aryan tribal alliance.

Dynastic Shifts and Aryan Intrigues: From Pradyota to Haryanka, Harappan Rule Back in Ancient Magadha

Ujjaini served as the capital of the venerable Avanti kingdom, counted among the sixteen Mahājanapadas of ancient times. Punika, a Harappan hailing from the coastal regions of present-day Gujarat (known as the Abhira people), served as a minister in Ujjaini’s court. Under the Videha Republic, Punika facilitated Chanda Pradyota, his son, to ascend the throne of Ujjaini in 546 BC. He became the founder of the Pradyota dynasty, also known as Prthivim Bhoksyanti, ruling over the Avanti Kingdom. Varttivarddhana marked the culmination of the Pradyota dynasty’s reign.

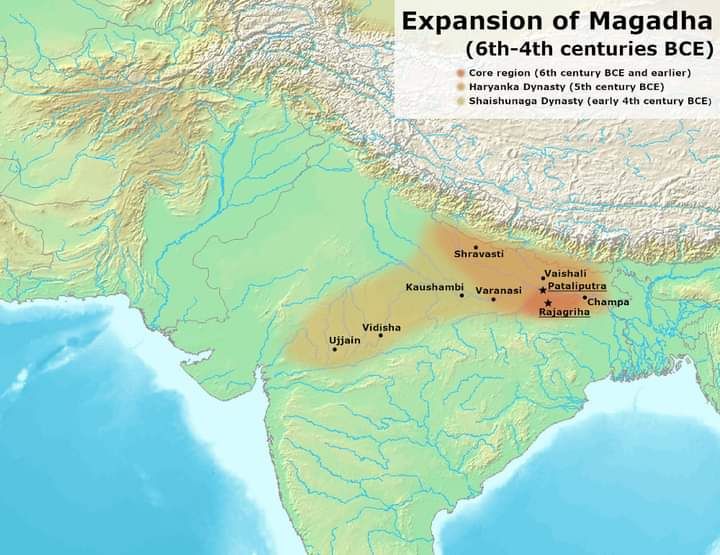

Subsequently, Bhattiya, a regional sovereign and minister within the Avanti dynasty, appointed his son Bimbisara as king at the tender age of fifteen. Bimbisara, in turn, became the founder of the Haryanka dynasty. The nomenclature “Haryanka” derives from “gramakas” (village headmen) overseeing village assemblies and “mahamatras” (high-ranking officials) entrusted with executive, judicial, and military responsibilities.

As the third ruling dynasty of Magadha, the Haryanka dynasty initially established its seat in Rajagriha. However, the capital was later relocated to Pataliputra, situated near present-day Patna in India.

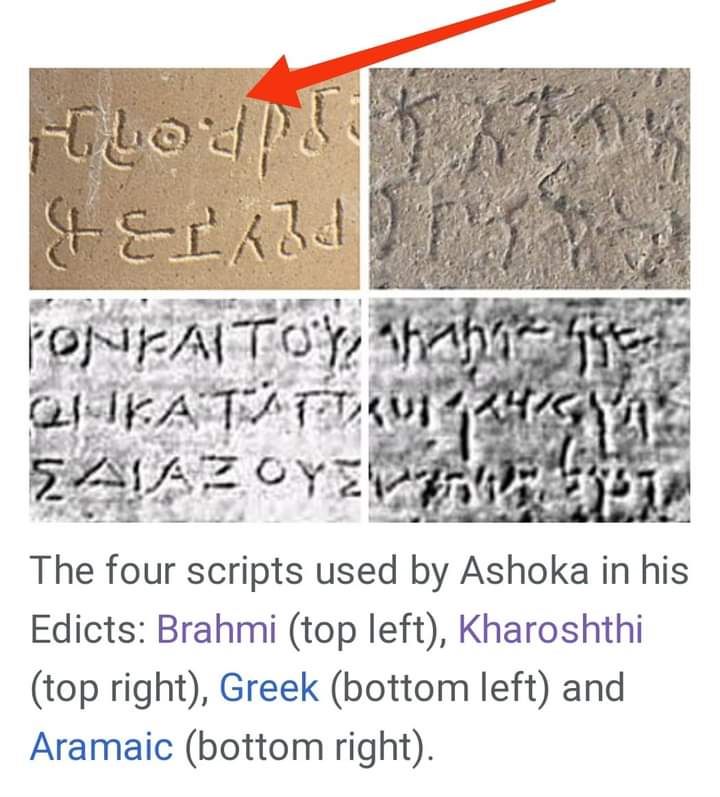

Terracotta pieces bearing Brahmi script, depicted in the fifth image, were unearthed at the Konthagai archaeological burial site, a component of the Keeladi Civilization near Madurai. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating conducted by the Beta Analytic Lab in Florida places the Keeladi civilization between 600 BC and 100 AD. Ashoka utilized four scripts in his Edicts, as seen in the sixth image: Brahmi, Kharoshthi, Greek, and Aramaic. The utilization of the Brahmi script by Ashoka serves as additional evidence that people across South Asia spoke Thamizh. It is plausible that the original local language spoken by the descendants of Bhattiya underwent a transformation, evolving into a Dravidian language currently known as Kurukh / Oraon / Uranw (Northern Thamizh – வட தமிழ்).

Nāgadāsaka, reigning from 437 to 413 BC, marked the culmination of the Haryanka dynasty’s rule.

Achaemenid Ambitions: Persia’s Intrusion, Darius’ Resurgence, and the Re-Consolidation of ‘Aryavarta’

During Bimbisara’s reign, India encountered another Aryan incursion, this time from the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, led by Cyrus the Great. Following a brief hiatus after Cyrus’ demise, the campaign resumed under Darius the Great. Darius embarked on reclaiming former provinces and expanding Persia’s political frontiers. Around 518 BC, Persian forces, under Darius, traversed the Himalayas into India, marking a second phase of conquest by annexing territories up to the Jhelum River in Punjab. These invasions spurred the re-consolidation of Aryavarta, originally established by Aryan tribes after entering into India.

Shishunaga’s Coup: Reclaiming Vaishali and the Ascension of Aryan Rule Back in Ancient Magadha

Shishunaga, an Amatya (minister) in the court of King Nagadasaka, hailed as the son of a Licchavi Aryan ruler of Vaishali and nurtured by an officer in the Haryanka kingdom, orchestrated a coup to depose Nagadasaka and ascend to the throne. Establishing the Shishunaga dynasty, he reclaimed Aryan hegemony in Vaishali. While the initial capital was Vaishali, it later shifted to Pataliputra, near present-day Patna.

During Kalashoka’s reign, he divided his realm among his ten sons and crowned Nandivardhana, his ninth son, as the ruler of Magadha. Following Nandivardhana, his son Mahanandin assumed the kingship of the Shaishunaga dynasty.

Legacy of Daimabad: Dravidian Aspirations amidst Aryan Dominion

Following the relinquishment of the Peoples’ Co-operative Harappan Republics of Daimabad, situated on the left bank of the Pravara River, a tributary of the Godavari River, to the Aryans, a profound unease pervaded among the indigenous youth residing between the Godavari and Narmada rivers. Despite their concerns, successive Aryan tribes solidified their dominions, leaving the native inhabitants in a state of resigned acceptance. However, within the hearts of the Dravidians, a fervent desire to overthrow the Aryan kingdom persisted.

Uprising of the Nandas: A Saga of Dravidian Ambition, Guerrilla Warfare, and Elephantry Triumph

One of the ambitious young men yearning to reclaim sovereignty from the Aryan tribes was Ugrasena Nanda, along with his eight brothers hailing from present-day Nanded, Maharashtra. Greek sources indicate their Sudhra background, highlighting the Aryan imposition of caste systems upon the local populace. According to the Mahavamsa, Ugrasena, the dynasty’s progenitor, and his eight brothers clandestinely assembled an army to seize control over territories held by King Mahanandin.

Engaging in guerrilla warfare within Mahanandin’s palaces, Ugrasena had a chance encounter with the queen of the Shaishunaga dynasty during one such expedition. As per Roman historian Curtius from the 1st century AD, King Mahanandin’s wife, captivated by Ugrasena’s alluring appearance, promptly developed affection for him. She actively supported the Nandas in their quest to capture the kingdom.

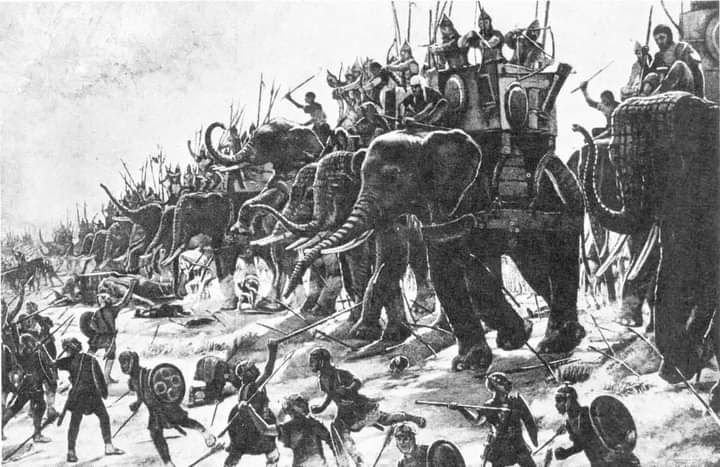

The Aryan tribes possessed cavalry forces, providing them with a strategic advantage over the indigenous inhabitants, who faced challenges in acquiring horses. Recognizing the necessity for a formidable battalion to effectively contend with King Mahanandin, Ugrasena discerned the need for an alternative. The chosen solution was elephantry.

The Gond people of Chanda willingly extended their support to the Nanda brothers in the pursuit of capturing and domesticating elephants, a resource deemed crucial for their military endeavors. Subsequently, other Gond communities also joined the initiative. Within the confines of the jungle, the Nandas underwent rigorous military training while mounted on the backs of elephants.

The wife of King Mahanandin discreetly divulged secret routes into the palace to her paramour, facilitating the Nandas’ seamless assassination of King Mahanandin and the subsequent capture of the kingdom in 345 BC. Successively, all the Nanda brothers assumed rule, fortifying their Elephantry units to forestall any potential Aryan incursion.

Dhana Nanda’s Elephantry Deterrence: Alexander’s Hesitation, Taxation Woes, and the Maurya Empire’s Genesis

During Alexander the Great’s invasion of India, Dhana Nanda held the reins of power. Hesitant to venture into Nanda territories due to their formidable elephantry units, Alexander’s troops, inexperienced in handling war elephants, refrained from extending their expedition further. Following his triumph over Porus (Shurasena), an Indo-Aryan king, Alexander restored the territories to him and appointed Seleucus I Nicator to govern his satrapies in Northwestern India.

Sustaining substantial elephantry units necessitated Dhana Nanda to allocate a significant portion of his exchequer, leading to heavy taxation on the populace. The resultant discontent among the people provided Aryan magus, Chanakya, who followed Jainism with an opportunity to turn the subjects against Dhana Nanda. In the end, aided by Chandragupta, Chanakya masterfully orchestrated the demise of the Nanda Empire, thereby laying the foundation for the establishment of the Maurya Empire. This decisive turn of events firmly closed the prospect of re-establishing a Dravidian empire in Northern India, except the four Gond kingdoms that existed till the 20th century.

Conclusion

The ongoing struggle that originated around 5000 BC in Arjika persists in various forms. Despite India’s introduction of Social Justice Empowerment measures, such as reservations in government jobs and educational institutions, a truly level playing ground has yet to materialize. This necessitates further extension of empowering measures, potentially through a caste-based census. The Aryan Magi, who historically wielded influence over kings, still occupy prominent positions across all pillars of democracy, contributing to a skewed democratic landscape in India. Understanding this historical context is crucial for the younger generation.

Megathenis spent several years in Padaliputhiram, offering a vivid portrayal of India. According to him, during his stay, people were restricted from changing their professions, laying the foundation for the caste system and associated discrimination. Megathenis’ book sheds light on ancient India,

indicating that among the Thamizhs, who inhabited all over South Asia, there was initially no caste system. For those interested in delving further, I’ve uploaded an e-book: ‘Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian’ in PDF format; please download from the following link:

https://m.facebook.com/groups/374316796239632/permalink/2154370744900886/?mibextid=2JQ9oc

This article is a tribute to Mr. Arikukkarasu, a stalwart of the Dravidian movement, who passed away recently. An avid reader of my blogs, he consistently provided encouraging feedback and held high hopes for my endeavors. Time alone will reveal whether I lived up to his expectations.

I extend my Dravidian Black Salute in homage to Mr. Arikukkarasu, a prolific author who remained active until the final hours of his life, having penned several books.

Published under International Cooperation with "Sindh Courier"

Comments