When I witnessed the deteriorating situation of our people, I seriously considered joining politics – Dr. Hamida Khuhro

[Translator’s note: This is a translation of renowned historian Dr. Hamida Khuhro’s comprehensive interview, originally published in the Sindhi magazine Nao Niapo, Karachi in May, 1986. The interview panel consisted of Advocate Masood Noorani (MN), Journalist Nasir Aijaz (NA) and Faqir Muhammad Lashari (FM), with Mansoor Qadir Junjo’s assistance to the interviewers. Masood Noorani also contributed observation notes from his initial meeting with Dr. Khuhro, which were used as a preamble to the interview. The interview was later included in an anthology that contained interviews of Dr. Khuhro, published in various Sindhi newspapers and magazines.

In 2021, Dr. Hamida Khuhro Foundation, Sindh (Karachi-Hyderabad) published Nao Napo magazine’s interview as a separate booklet with a title of ‘Tareekh Ji Amhon Samhon’ (Face-to-Face with History). The booklet includes a preface by Mansoor Qadir Junejo. Zaffar Junejo]

MN: I would like to know about your political journey. When and where did you start it?

KH: I began my political journey in 1971.

MN: Did it happen because of Bangladesh?

HK: Yes, although emotionally, I was aligned with the Muslim League. My father was a politician, and I had the opportunity to meet many politicians. However, I never had the intention of pursuing a political career. It was only when I witnessed the deteriorating situation of our people that I seriously considered joining politics. Sindh was facing oppression, and there was a great threat to the Sindhi language. H.T. Lambrick once reminded me of plans for the preservation of Sindhi language. He warned that Sindhi language was under threat, with a leading cause being the influx of outsiders. Additionally, there was an assumption that as long as Bengal remained with us, something positive might occur. This belief was based on the fact that Bengalis constituted a majority of the population. When the Pakistan Army took action in Bangladesh, I was in London. It was then widely believed that Bengal would no longer remain a part of Pakistan. At that moment, I realized that if Bengal was to separate, our position would be severely weakened and compromised. I couldn’t comprehend how we were letting go of our grip. It became clear to me that it was the right time to speak my mind, and I saw it as a last opportunity. Consequently, we decided to take measures and actions. We issued press statements, called upon Sindhis based in London, and I personally wrote letter (s) and an article.

In East Pakistan, the bureaucracy denied people their basic democratic rights

MN: What do you believe were the reasons for the separation of East Pakistan? It is an age-old question, but we would like to hear your opinion.

HK: In East Pakistan, the bureaucracy denied people their basic democratic rights. During the ten years of Gen. Ayub Khan’s regime, their resources were exploited, and Bengalis were excluded from any meaningful political process. This raised an important question: ‘when you are neither consulted nor respected, you become mere puppets, without any real significance.’ In such circumstances, independence becomes an inevitable choice. Although the Bengalis had achieved success in the Bengali Language Movement, but they were still treated as subjects by the Punjabis, who always considered themselves superior to the people of Bengal. The condescending behavior and derogatory language was used towards the Bengalis – what Sindhis are currently experiencing – being labeled as infidels and inferior. The Bengalis had been struggling for their rights for a long time, and we must not forget that their geographical position worked in their favor and contributed to their eventual independence.

It is a fact that if Sindh had not been separated from Bombay, there would have been bleak chance of establishing Pakistan

It is a fact that if Sindh had not been separated from Bombay, there would have been bleak chance of establishing Pakistan

MN: Allama Iqbal’s Allahabad speech in 1930 laid the foundation for Pakistan, but Bengal was not included. Similarly, Choudhary Rahmat Ali’s Pakistan scheme also excluded Bengal by omitting the letter ‘B’. So, it seems that Bengal had to forcefully become a part of Pakistan. What is your opinion on this matter?

HK: There is some truth to that. As you may know, Rahmat Ali proposed multiple schemes, including Pakistan and Usmanistan. True, the letter ‘B’ was not included in Pakistan. His belief was that there would be independent states, as reiterated in the Pakistan Resolution, where all constituent units would be sovereign and independent. However, the resolution underwent changes in 1946. It was specified that there would be one state in the West, comprising of Punjab, Sindh, and Baluchistan. Similarly, the Eastern state would consist of Bengal and Assam. However, both states would have autonomous and sovereign constituent units. However, Lord Mountbatten’s June 3 plan divided Punjab and Bengal. At that time, Jinnah believed that Bengal could not survive on its own and should be part of Pakistan, so it was included. Additionally, the change in 1946 was proposed by some members of the legislative body who thought that running two separate countries would be difficult, and thus one Pakistan state should be formed.

MN: Sindh also played an important role in the formation of Pakistan, and G.M. Syed’s efforts in this regard were admirable. It is also claimed that Sindh’s separation from Bombay laid the foundation for the formation of Pakistan.

HK: It is a fact that if Sindh had not been separated from Bombay, there would have been bleak chance of establishing Pakistan. It is also true that until 1946, apart from Sindh and Bengal, no other province supported the idea of Pakistan. In the East, only Bengal supported it, while in the West, apart from Sindh, no other province voted in favor of Pakistan. So, Pakistan might have been formed in Bengal. However, Sindh’s separation from the Bombay presidency had its own reasons and was a century-old demand of Sindh.

There should be no doubt that Sindhis certainly participated in the Pakistan Movement

FM: It is known that Sindh did not fully participate in the Pakistan Movement, and even in 1943, the Governor’s nominees voted. I mean, not all steps were fair. What is your opinion?

HK: There should be no doubt that Sindhis certainly participated in the Pakistan Movement. To some extent, we can look at the Masjid Mazilgah case (Hindu-Muslim riots in Sukkur) in this regard. At that time, a Satyagraha took place, which transformed the movement into a Sindhi Muslims’ demand for Pakistan.

MN: Did it become a demand, or was it formulated that way? Jinnah played a leading role.

HK: (She smiled) It was in Jinnah’s interest. He was in favor of Pakistan.

MN: Committee number 9 was formed.

HK: Are you referring to the committee on Sindh’s separation from the Bombay Presidency?

Raees Ghulam Muhammad Bhurgri

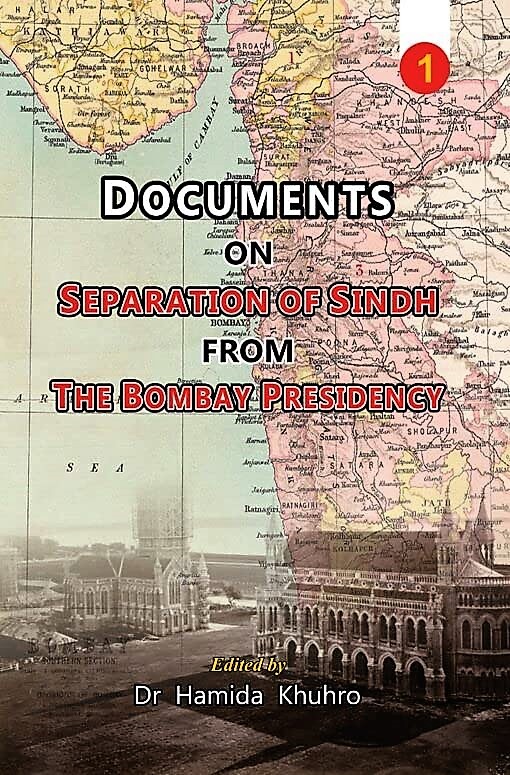

MN: Yes, I am referring to that committee. Jinnah was a staunch supporter of Sindh’s separation. He advocated Sindh’s case and convinced the members with his arguments. However, a separate committee was formed for financial matters. In that regard, your father also wrote a letter to Allama Iqbal for support, and he assured his assistance. I have read all about this in your book, ‘Documents on Separation of Sindh from the Bombay.’

HK: It is a story of old times. In fact, Jinnah visited Sindh around 1929/30 regarding the case of Pir Pagaro. Sindhi Muslims hosted a dinner in his honor at Pir Sahib’s Bungalow in Khairpur Mirs. During that meeting, Muslim leaders requested Jinnah to advocate for the separation of Sindh and asked for his support. This happened before the All Parties Conference in Calcutta. Later, when Jinnah was going to attend the First Roundtable Conference in London, another dinner was hosted in his honor, where he was again requested to highlight the case for Sindh’s separation. After that, Jinnah did not take much interest in the political scene and focused on his personal affairs. Therefore, he was not present at the Second and Third Roundtable Conferences. In subsequent conferences, representatives from Sindh participated, including Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto (although he had initially opposed Sindh’s separation before the Simon Commission) but later agreed. Others who attended the Roundtable Conferences were Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, Sir Aga Khan, and my father. Thus, we can say that the separation of Sindh was agreed upon and advocated by all, even opposition politicians agreed. Finally, Ramsay MacDonald also agreed to Sindh’s separation. We can say that there might have been some political compromises in the whole affair.

MN: It proves that the political acumen of the Hindus was much more advanced?

HK: In this particular case, we cannot say so.

Seth Vishandas

MN: I think the first proponent of Sindh’s separation was Seth Vishandas. He, along with Raees Ghulam Muhammad Bhurgri, advocated for Sindh’s separation from Bombay, but later he withdrew his support.

HK: Yes, he initially supported Sindh’s separation on administrative grounds. Later, he realized that in the event of Sindh’s separation, Hindus would become a minority and Muslims would be in the majority. After that realization, he withdrew his demand for Sindh’s separation.

MN: It wouldn’t be correct to state that the Jagirdars and Waderas of Sindh were under the influence of the English government and the exploiting class of India, and that is why they launched the struggle for Sindh’s separation from Bombay. They were active in protecting their own interests and didn’t care about the disastrous results. They thought this way because Hindus were everywhere – in trade, employment, politics, and councils – they also had a middle class.

HK: That is your opinion, but I don’t agree with that idea.

Sindh became a hunting ground for English officials, and winter became their hunting season

MN: Then what is your opinion?

HK: Sindh was an independent land. It was conquered by the English and remained independent until the period of Charles Napier. Then, it was made part of the Bombay Presidency. Sindh became a hunting ground for English officials, and winter became their hunting season. If we retrospectively look at the struggle for Sindh’s separation, we will come across the struggles of Raees Ghulam Muhammad Bhurgri, who was a nationalist and associated with the Indian National Congress. He was not a puppet of the English government. You can see reports from Sir Henry Lawrence, who wrote against him and categorically mentioned him as an opponent of the British government. During that time, Bhurgri and another leader of Sindh, Seth Vishandas, advocated for Sindh’s separation. The separation movement was also supported by other Hindu leaders, like Dayaram Gidumal. We should not forget that in 1913, the Indian National Congress held its session in Karachi, and in its first session, the separation of Sindh from Bombay was discussed and demanded. So, how can you assume that the struggle was patronized by the English? Perhaps you thought so because Sindh’s separation became beneficial for the Muslims. (Continues)

Click here for Part-I and Part-II (Preamble) – Part-!II , Part-IV , Part-V , Part-VI

Published under the International Cooperation Protocol with Sindhcourier

Comments