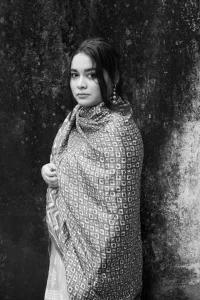

A new book by psychologist Scherezade Siobhan ‘That Beautiful Elsewhere’ spotlights the sociocultural factors and everyday stresses that can lead to mental illness, juxtaposed with a broken psychiatric system in India.

We are all storytellers who live and share stories of ourselves and of others. But there are some stories that we don’t share. These are often stories that we involuntarily tell ourselves, over and over again, despite our best efforts to forget or repress them.

Sometimes, if we are lucky, we find a safe space as in psychotherapy, to voice them out, to reframe and integrate in confidentiality and in the presence of a non-judgmental empathetic witness who can help us navigate the turbulent waves of psychological distress.

That Beautiful Elsewhere (HarperCollins India, INR 499) is a collection, or rather a recollection, of stories of struggle that we don’t tell others. Authored by Mumbai-based psychologist and writer Scherezade Siobhan, this new bare-it-all memoir is rooted in the courage of “radical vulnerability”, interwoven with carefully and ethically narrated experiences of some of her clients.

The 10 chapters attest to the author’s intent to aim for “catharsis without pageantry”. Each chapter has an overarching subject where the reader gets more than a peek into some relative therapy sessions. There are no beginning-to-end stories but instances or excerpts from larger ones stitched together with reference material from psychology and neuroscience, which help the reader understand the intricacies of the subject.

Almost every chapter has sections through which the author reveals her personal struggles. The subjects covered encompass the “lived experience” of several mental disorders (including schizophrenia, mood disorders like major depression, anxiety disorders, trauma related disorders including PTSD and C-PTSD, personality disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders).

The book delves into subjects of loneliness, suicidal ideation, isolation, shame and stigma associated with mental health in Indian society, especially the label of ‘madness’ allotted to those who speak about their condition.

She also covers struggles with auto-immune disorders, adverse childhood experiences and abuse, the struggles of being queer in the Indian sociocultural demographic, mental-health implications of violence against women, the plight of sex workers and transgender community in the country and the collective trauma of living through a global pandemic.

Further, the book delves into subjects of loneliness, suicidal ideation, isolation, shame and stigma associated with mental health in Indian society, especially the label of ‘madness’ allotted to those who speak about their condition.

It also raises the mental-health hazards of caste- and class-based oppression and discrimination, arranged marriages, the structure and mechanisms of an average Indian family, and intergenerational trauma in a complex social and cultural fabric.

This book can be a resource of available care and support systems in the country while being a healing experience in itself. Yet, multiple times, the author alludes to the inadequacies of a broken psychiatric system that relies heavily on a biomedical model without giving much importance to the psychosocial influences.

This results in things like over-anthologizing and misdiagnoses. “That better elsewhere is not a place but a direction,” writes Siobhan. For fostering genuine healing, there has to be a treatment modality which is decentralized, combines community involvement with psychiatric care and does not overlook the significance of sociocultural aspects of causation.

Compassion for people suffering from mental illnesses should not be limited to a therapy room, it has to be embedded in the community. We must raise awareness and alter perceptions, so people are not left alone without familial and communal support to deal with the discord of psychopathology. “The simplicity of a hand held out without questions is the first step of the journey. To find more hands along the way is the rest of it,” Siobhan says.

Reading through, I quite appreciated that, at no point, does the author separate the workings of the human mind from the workings of human life. “The Superego walks into the room first, reminding us that we are all puppets strung on thin threads of social conditioning,” she notes, and, “… harm isn’t always rooted in pathology.”

Instead of symptoms, there is poetic prose describing their manifestation as life conditions: “You can’t shun experience. You can’t suture the ways in which it rips you apart. Like an animal that hides in a ditch till the fractured bone heals, I am given to waiting these days.”

The author has included words from languages other than English to describe certain emotional states that I found quite appealing. These words do not have a singular substitute in the English language but have been roughly translated.

The imagery and candour in the book are deeply engaging, at times engulfing. It is impossible not see a bit of yourself in her words. I felt compelled to put the book down periodically because absorbing too much truth in one go is not easy. The rich use of language drove me to pick it up again.

The author has included words from languages other than English to describe certain emotional states that I found quite appealing. These words do not have a singular substitute in the English language but have been roughly translated.

Boghz in Farsi is ‘the physical building up of sorrow and pain in the chest/throat before crying’. Iyari in the Huichol dialect refers to “heart memory” that we are born with. The Korean word Han stands for “ache and bitterness” or “mourning and release” and can even mean “helplessness and dissatisfaction”. Lastly, the Urdu term tabeer, which is also the title of the last chapter, refers to “the interpretation of a dream”.

Siobhan shares, “On days that I can’t emerge fully, I try to offer my life to tabeer. A dream still unfolding, a rose unfurling the first of its many tongues. I teach myself a deepened vehemence: for chance, curiosities, and pluralities. I don’t fight to belong in a world that beats me down. I start building a world of my own” – a beautiful elsewhere.

I came across a riveting quote by author Alain de Botton, “A healthy mind knows how to hope; it identifies and then hangs on tenaciously to a few reasons to keep going. Grounds for despair, anger, and sadness are, of course, all around. But the healthy mind knows how to bracket negativity in the name of endurance. It clings to evidence of what is still good and kind. It remembers to appreciate.”

The quote is a reminder that hope is the ember of life, even if others consider it as utterly delusional. Else is hope. If one thing doesn’t work out, something else will. Elsewhere is hope, it is another space of possibilities.

And that is what That Beautiful Elsewhere is, a book about hope – not just in clinging to what is evident but about unearthing and unwrapping and even creating hope to feel and to get better.

Published under International Cooperation with "Sindh Courier"

Comments