The Dhatki language is spoken in Thar Desert. Exploring 4 Endangered Languages of India

By Aakanksha Gupta and Sakshi Sharma

Did you know that languages, like animals, can be endangered? When there are less than 10,000 people speaking a tongue, it is more likely to disappear! According to research from the United Nations, an indigenous language dies every two weeks.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) states, “A language is endangered when its speakers cease to use it, use it in fewer and fewer domains, use fewer of its registers and speaking styles, and/or stop passing it on to the next generation.” They subcategorize endangered languages as the following:-

- Vulnerable

- Definitely endangered

- Severely endangered

- Critically endangered

- Extinct

So how do languages become extinct?

The following are a few reasons we found:-

Languages are endangered by external threats (e.g. military and religious control) or internal threats (“a community’s negative attitude towards its own language,” as per UNESCO).

State and central governments don’t recognize regional languages and don’t implement them into education systems.

Levels of migration increase and urbanization speeds up, causing a loss of traditions and the increase in pressure to speak a more dominant language for social and economic growth.

When a particular group of people gains social and cultural dominance, their language becomes more widespread. For example:

– Sanskrit was widely spoken in ancient India.

– English was popularized by the British government.

– Hindi, in Khari Boli form, was deemed the language of Hindus during colonial rule.

When a community isn’t literate, it relies on oral traditions rather than a written language, making it more likely to vanish when the speakers dwindle.

Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going. — Rita Mae Brown

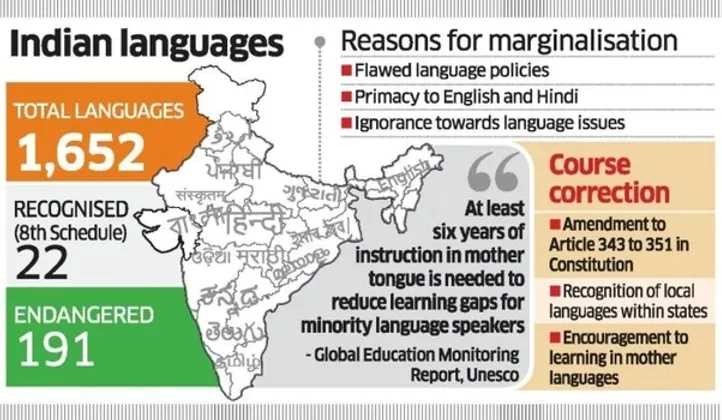

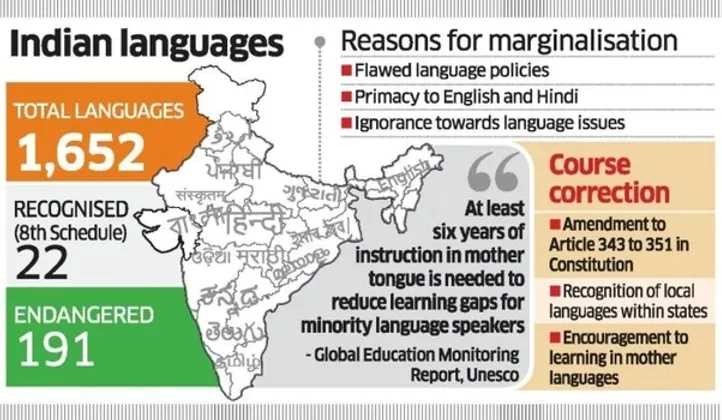

Following the 1971 Census of India, the government determined that languages spoken by less than 10,000 people would not need to be included in the official list of languages. Presently, the Indian Constitution’s 8th Schedule only recognizes 22 major languages. Starting in 2010, Ganesh Narayan Devy (a well-known artist and literary critic) explored the linguistic diversity of our country through the People’s Linguistic Survey of India. Devy recorded 780 languages, of which 600 were dying languages. In addition, 250 have been obsolete since 1950. Though as Devy points out, the advent of printers highlighted a limited number of languages, leaving the others less recognized.

UNESCO’s Atlas of the World Languages in Danger states that around 197 Indian languages are currently in danger, making it the highest of any country in the world. In 2013, our government enacted the Scheme for Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages (SPPEL). Helmed by the Ministry of Education’s Language Bureau, the SPPEL is facilitated by the Central Institute of Indian Languages in Mysuru, Karnataka. The initiative is preserving and documenting languages that are endangered or on the verge of endangerment. The SPPEL’s ongoing phase is monitoring 117 languages, with 500 more lesser-known languages on the horizon.

Below is a list of four Indian endangered languages that piqued our interest:-

Mahasu Pahari

Mahasu Pahari or Mahasuvi is one of the western Pahari languages with origins in the Mahasu district of Himachal Pradesh. Like all other Pahari languages, Mahasuvi’s history goes back to the Maurya period, i.e. 4th century BC.

The language was originally recorded in Takri script, but due to modern distortions and convenience reasons, it is now written in the Devanagari script.

Its decline can be attributed to the Colonization of Lands Act which was levied upon Himachal Pradesh in 1912. After this, schools and offices in the area could only function in languages “approved” by the British government, which excluded all the native tongues of Himachal.

Ever since, Mahasu Pahari has been facing a consistent decline, and is now used only for informal communication in domestic and religious settings. Left with less than 900,000 native speakers, Mahasu Pahari was classified as an endangered language by UNESCO. To restore it to official usage, the Indian government recently declared it a dialect of Hindi.

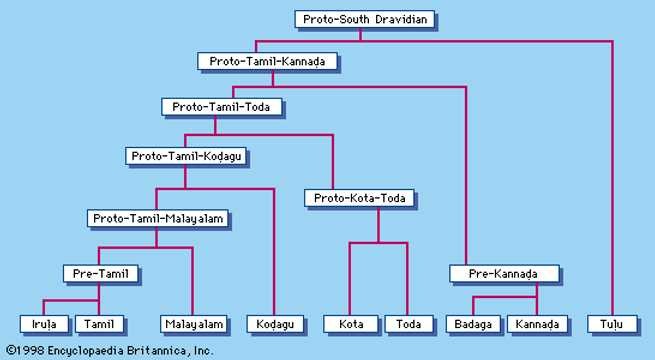

Kota

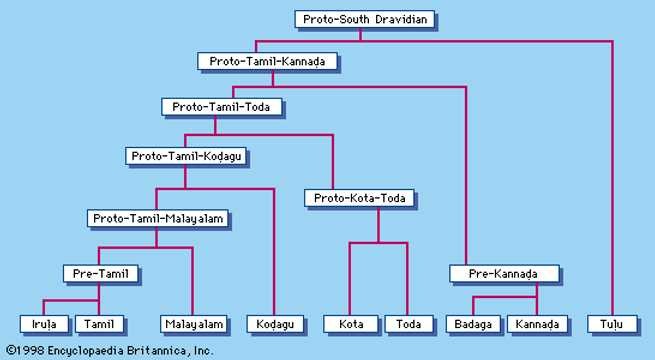

Kota is a tribal Dravidian language with roots in the Nilgiri hills of Tamil Nadu. The Kota people are indigenous to seven villages across the mountain range.

After the establishment of capitalism in the early 19th century, the village saw a steep decline in its population and their legacy-based traditional learning. Urbanization crumbled the thriving tribe of musicians, potters, laborers, and ironsmiths that constituted the Kota community. As the culture died, the language started to as well.

The Kota villagers are now a tribe of agriculturalists whose total population, since the last decennial census, is 300 people. The language now sustains itself through these 300 natives and has hence been declared a critically endangered language.

In 2011, a priest single-handedly wrote and published two books in a dialect of the language to keep the script alive in the world outside the Nilgiris.

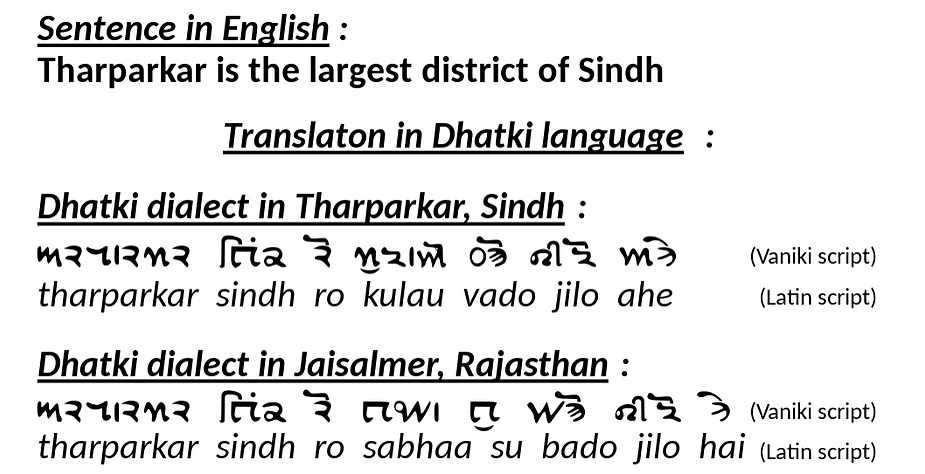

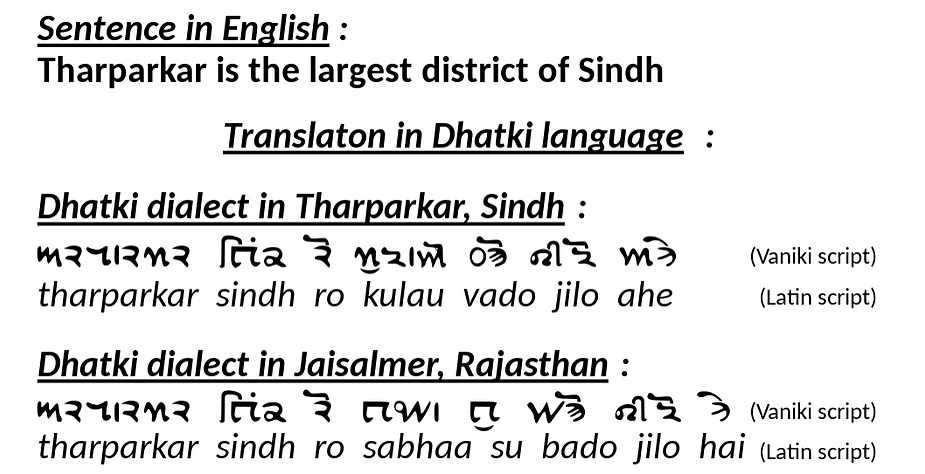

Dhatki

The Dhatki language (also known as Dhatti or Thari) can be traced back to the Maheshwari and Sodha Rajput communities of the undivided Thar Desert. Once spoken by lakhs of people among these communities, Dhatti is now spoken by a few hundred families in the Gadra and Shiva districts in Barmer.

The plight of its native speakers is particularly tragic. During the Indo-Pak partition, they became part of two groups — refugees in Rajasthani shelters or Hindu minorities across the border enduring constant incursions. This destruction of collective identity caused a drastic drop in the number of Dhatki Speakers.

Many descendants of the refugees and natives are actively seeking a government initiative for the revival of their native tongue. They believe that the language and folklore can be brought back if integrated into a script.

Toto

Toto is a Sino-Tibetan language native to the Totopara tribe in West Bengal. Listed as a critically endangered language by UNESCO, Toto is spoken by only over 1000 people.

The origin of its decline was marked by the Linguistic Survey of India by the Irish linguist and Officer George Grierson. In his survey, Grierson classified Toto as a “non-pronominalized Himalyan language,” meaning that it was deemed too insufficient to become an official language. As a result of this, the British government disbarred Toto from official usage and replaced it with Nepali and Bengali.

In a pioneering attempt to bring the Toto language back to life, author Charu Chandra Sanyal published a book in English called The Meches and The Totos in 1972, wherein she dove into the history, beauty, and decline of the Toto language.

Language is the most fundamental part of human cognition, communication, identity, and history. Over time, languages constantly evolve with their societies and cultures. Since language is such an integral part of the story of the human race, we hope that our communities and education systems can promote endangered languages.

Published under International Cooperation with"Sindh Courier"

UAE shines as global incubator for startups in smart mobility solutions

UAE shines as global incubator for startups in smart mobility solutions

Blast at mosque in Nigeria kills 5, injures over 30

Blast at mosque in Nigeria kills 5, injures over 30

UAE marks 2025 with global competitiveness milestones

UAE marks 2025 with global competitiveness milestones

Japan expects growth to accelerate next year with fiscal stimulus

Japan expects growth to accelerate next year with fiscal stimulus

OPEC Fund to co-finance up to $2 billion to accelerate development across Africa

OPEC Fund to co-finance up to $2 billion to accelerate development across Africa

UAE-EU Dialogue on Human Rights holds 13th meeting in Abu Dhabi

UAE-EU Dialogue on Human Rights holds 13th meeting in Abu Dhabi

UAE condemns terrorist attack in northwestern Pakistan

UAE condemns terrorist attack in northwestern Pakistan

UAE shines as global incubator for startups in smart mobility solutions

UAE shines as global incubator for startups in smart mobility solutions

Blast at mosque in Nigeria kills 5, injures over 30

Blast at mosque in Nigeria kills 5, injures over 30

UAE marks 2025 with global competitiveness milestones

UAE marks 2025 with global competitiveness milestones

Japan expects growth to accelerate next year with fiscal stimulus

Japan expects growth to accelerate next year with fiscal stimulus

OPEC Fund to co-finance up to $2 billion to accelerate development across Africa

OPEC Fund to co-finance up to $2 billion to accelerate development across Africa

UAE-EU Dialogue on Human Rights holds 13th meeting in Abu Dhabi

UAE-EU Dialogue on Human Rights holds 13th meeting in Abu Dhabi

UAE condemns terrorist attack in northwestern Pakistan

UAE condemns terrorist attack in northwestern Pakistan

Comments